Who will be the first Latin American president kicked off Twitter?

Technology companies' decisions over the past week related to Trump and his followers will raise new questions about content moderation across the region.

Last week I wrote about how the insurrection effort that led to five dead in the US Capitol impacts democracy around the hemisphere. The issue will also impact technology policy and regulation in other countries in the months to come.

Technology companies took action in the last week including:

Donald Trump was banned from Twitter, Facebook and other social media platforms for inciting violence.

Apple and Google removed Parler, a platform where violence was organized, from their app store and Amazon Web Services stopped hosting the app, forcing it offline.

Stripe stopped processing payments for Trump’s campaign website.

These are big moves by technology companies that have led to two legitimate competing points of view:

Is it fair these US-based companies have so much control over people’s ability to express themselves on the internet and should their de facto ability to censor certain groups be restrained through regulation?

What the hell took them so long and why don’t they do more?

That first point of view is one that deserves a significant consideration and takes on extra significance in Latin America where there is sensitivity to sovereignty issues and having US actors take decisions that impact the region. There are also concerns by pro-democracy activists that decisions made in the US in the past week could be used by more repressive regional governments to justify censorship.

The second point of view is one that will be more widely debated over the coming months across the region. Near the end of the campaign, Trump was heavily regulated, with numerous tweets receiving warning messages. Then he was banned before a single Latin American leader was kicked off the platform. Perhaps banning presidents was not viable before 2021, but the phrase you’ll read a lot in 2021 is “Trump got kicked off for less.”

Trump got kicked off for less

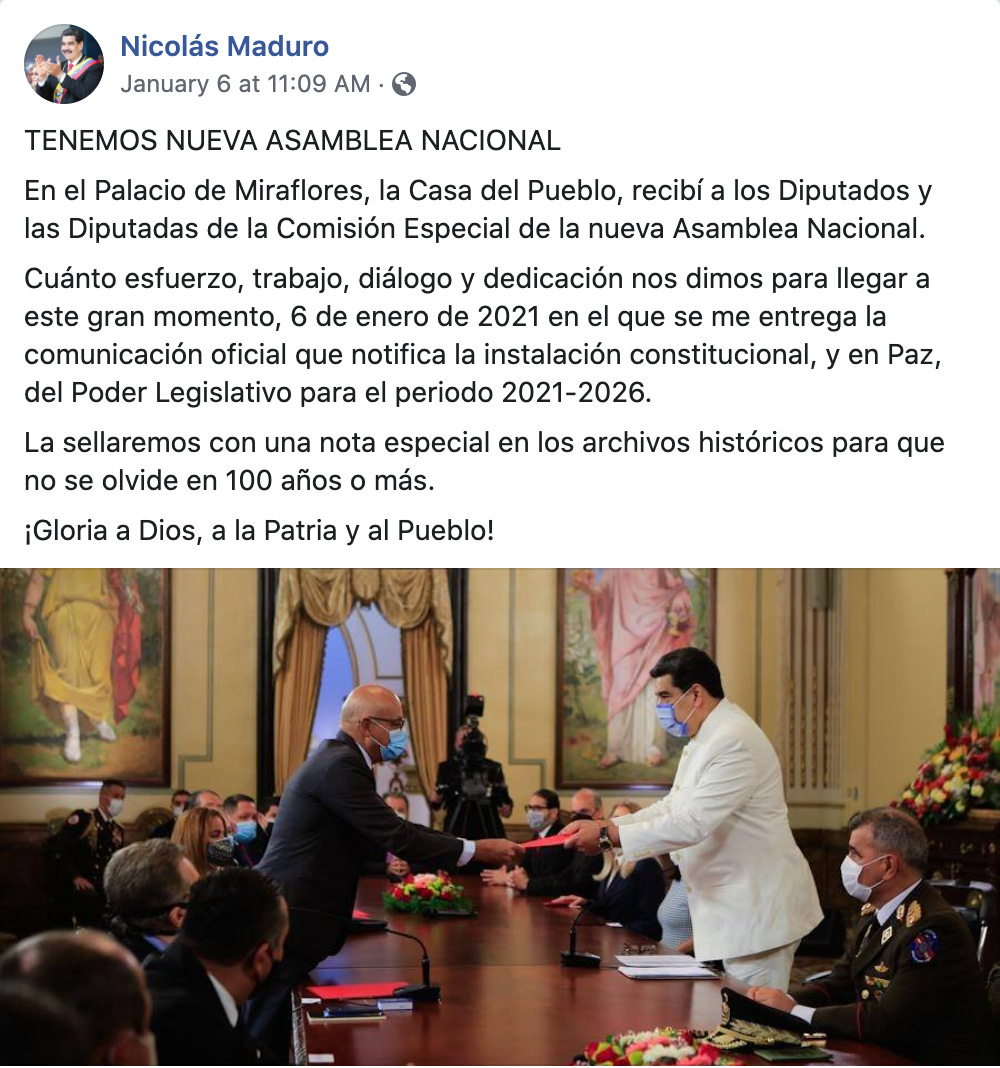

Venezuela - Just in the past week, Maduro has posted numerous social media claims that his party took control of Venezuela’s National Assembly, something that is disputed by his political opponents and by a good number of international actors including the EU, US and OAS. Hundreds of political opponents have been threatened, jailed, killed or forced into exile. On multiple occasions, Maduro sent military and paramilitary forces to harrass or attack political opponents including some at the National Assembly building. As far as I can tell, not a single one of Maduro’s messages on Facebook or Twitter over the past week was removed or received a warning noting that his claim on the election was in dispute.

Above: Post from Maduro’s Facebook page promoting the disputed new National Assembly

Maduro allies have also used social media postings to threaten critics and direct violence. During the last election, Diosdado Cabello, for example, promoted videos in which he threatened to withhold food from people who did not vote for the regime. He is among those who have used hashtags promoting FAES violence including one that is a reference to the knock on the door from the police forces prior to detaining or killing people. The FAES killed over 20 people in a raid over the weekend and were responsible for a significant portion of Venezuela’s murders in 2020 according to NGO statistics.

El Salvador - Trump sent an angry mob to the Congress. Bukele sent the military. The president of El Salvador gloated on social media as he sent military forces into the Congress last year to pressure his political opponents during a debate over debt. Then he set up bots to promote his own point of view.

Cuba - Miguel Diaz Canel is quite professional and polite on his social media feed, far more reasonable than his counterparts in the US, Brazil, El Salvador or Venezuela. He also runs a dictatorship that brutally beats and jails its political opponents and hasn’t held a free election with real political opposition in over 60 years in power. Do dictators with good online etiquette deserve better treatment than impolite leaders elected democratically?

Honduras - Juan Orlando Hernandez robbed a bunch of government money for his political party, stole an election, used the military to repress his political opponents, and runs cocaine for profit. According to media reports, he is also among the leaders in the region paying for botnets to attack his critics.

Mexico - Enrique Peña Nieto’s PRI set up large online operations to manipulate trending topics and harass political opponents. Then AMLO copied him. The Peñabot vs Pejebot battles may seem like a cute online distraction, but Mexico is also the most dangerous country in the world for journalists and among the most dangerous for other types of activists. Threats online, including critiques of specific critical journalists by political leaders, translate to violence in the real world much more easily in a country where most crimes are never prosecuted.

Nicaragua - The Ortega regime has undermined democracy. It also sent police and paramilitary forces to kill and wound hundreds of protesters who tried to demonstrate against the regime. Every social media platform has plenty of Sandinista propaganda with no warnings that the country’s democracy is in dispute or that those same party activists those social media feeds are promoting organized to commit gross human rights abuses against their opponents.

I could go on. Those attacks directed by government officials don’t even get into the questions about foreign-directed disinformation or the day-to-day harassment and threats received by hundreds of social activists, particularly women and minorities.

Regulation by technology platforms will likely change in 2021

It’s easy for me to write my newsletter selectively choosing examples that highlight areas where greater moderation should be done. It’s a whole lot harder to actually do the moderation and make the decisions that balance public security, democracy, freedom of expression and the public’s right to information.

That’s a long list of abuses by government actors up above. How many presidents or cabinet members or political parties should be moderated or even de-platformed? And if they are removed, does it make the whole platform less viable or interesting or useful? Putting resources into moderation in a high-profile market like the US or Mexico or Brazil is a different commercial decision than agreeing to carefully monitor democratic decline and political violence in Venezuela, El Salvador and Nicaragua. It would probably be easier and more profitable for platforms to just pull out of some smaller countries, and that would be a terrible outcome if it occurred. Nobody should want to push companies in that direction.

Countries across the region are going to have these conversations in 2021, citing the example in the US this January as the case for action when something awful occurs somewhere else. The examples cited above are things that already have occurred. I don’t know if companies are going to go back and review those incidents, but the real question is whether the next election or democratic crisis in Latin America is going to be treated differently by technology companies given the precedent set in the US this past week.

None of these are easy decisions, but technology companies that can afford to do so should treat these issues as if countries’ democracies and people’s lives depend on them. Because they do.

Thanks for reading

As I announced on Friday, yesterday’s newsletter on coronavirus was for paying subscribers only. So is tomorrow’s poll number roundup. Thanks to everyone who has paid to subscribe and support this newsletter. If you are not a subscriber and appreciate the content, please consider subscribing for $9 per month or $90 per year.