Nine takeaways from the IMF outlook on Latin America

High uncertainty and stagflation light will be narratives over the next two years.

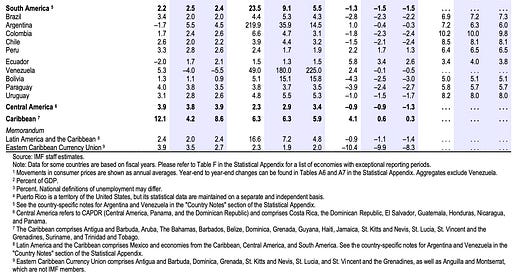

The IMF published its updated World Economic Outlook this morning. Here is the relevant chart for Latin America.

Key points

The IMF predicts a recession in Mexico. Growth estimates for Mexico have dropped by 1.7 percentage points since their last publication in January. Mexico is now expected to be at -0.3% GDP this year and only 1.4% growth in 2026. It was expected. It’s going to be a problem for Sheinbaum. Mexico will need to run a deficit to stimulate the economy and help the social safety net for those hit by the economic damage (and keep the president popular). It also needs to pay its Pemex debt. Mexico’s Central Bank can’t respond to the economic problems by dropping interest rates too quickly due to inflation and the strong currency. All of that means global financial markets aren’t going to be happy with the policies that Mexico will implement to counter the damage that is mostly caused by its neighbor to the north. That creates a negative spiral.

Most of the rest of Latin America faces “stagflation light.” Growth remains positive in most countries, but it’s still slowing due to tariffs, the global economic slowdown, policy uncertainty, and the withdrawal of fiscal stimulus. Meanwhile, the “progress on disinflation has mostly stalled,” which is a nice way of saying that inflation remains too damn high in most countries.

For example, the IMF expects 2% GDP growth in Brazil and 5.3% inflation. In Colombia, it’s 2.4% growth and 4.7% inflation. Those numbers, which mostly continue into 2026, mean populations will feel the economy is doing poorly, even if it’s technically growing. Given that both Brazil and Colombia have elections in 2026, both governments are going to be incentivized to spend more to counter the economic problems and win votes. That could mean a short term boost to GDP in both countries above the estimates, but also higher inflation expectations for several more years.

Peru is a rare bright spot. The expected 2.8% growth and 1.7% inflation is not “Peruvian miracle” territory, but it is doing better than pretty much all of its neighbors. Given the recent economic and political challenges in the country, they’ll take it.

The Bolivian economic crisis is real. 1% growth and 15% inflation for the next two years is going to lead to political instability. There is no other way to read those numbers. If the opposition wins the election later this year, they will inherit an economic mess that will likely lead to public anger and swift political challenges. There is no quick and easy fix for those 2026 projections.

The IMF is optimistic about Argentina. GDP will grow 5.5% and inflation will only be 36% this year and 15% next year (only in Argentina could those inflation numbers be positive.

Cynical take: Of course the IMF is a big cheerleader and pumping up how awesome Argentina is. The IMF just gave another $20 billion to Argentina and therefore cannot afford to say anything that could cause a crash. It would be awful for the IMF balance sheet if they did. Obviously, the researchers writing this report are more independent than that, but I can’t help but be a little skeptical about the numbers.

During the press conference, a journalist asked why Argentina’s numbers remained high when everyone else saw a drop and the answer was essentially because everything is roses and unicorns in Argentina. However, the respondent also said that Argentina faces potential risks in terms of both domestic policy and global economic declines/uncertainty.

Food prices remain high. This sentence from the IMF report caught my attention: “A resurgence in food and energy price inflation, driven by commodity market fragmentation or intensification of climate-related disasters, could worsen living conditions and heighten food security concerns, particularly in low-income countries.”

Are we really talking about high food prices still? Yes. The FAO Food Price Index published in early April was at 127, higher than its average for 2024 or 2023. In real terms, food prices today are higher than they were during Arab Spring or any other time in the past 50 years. They have sustained at a high level for about five years now post-Covid, and they are creeping up yet again. Even though it feels like an old story, it’s a sustained high price story that is good for a few countries like Argentina and Brazil, but bad for much of the rest of the region.

Big trends ahead. The report has additional chapters on aging demographics and the impacts of migration and refugees on the economies. There are also comments on artificial intelligence and energy demand. I haven’t had a chance to read and think about all those yet. Just flagging them as big trends that will reshape economies beyond the two year projections.

Most Latin American currencies are stronger. The Trump administration wants the dollar to remain the world’s reserve currency, but it also wants a weaker US dollar. Its policies appear aimed and weakening the dollar relative to everyone else. A weaker dollar means that exporting to the US becomes a bit harder (regardless of tariffs, which are also an issue) and the purchasing power of remittances decreases. That will be bad for many low-income nations and will be a particularly hard hit on Mexico and Central America.

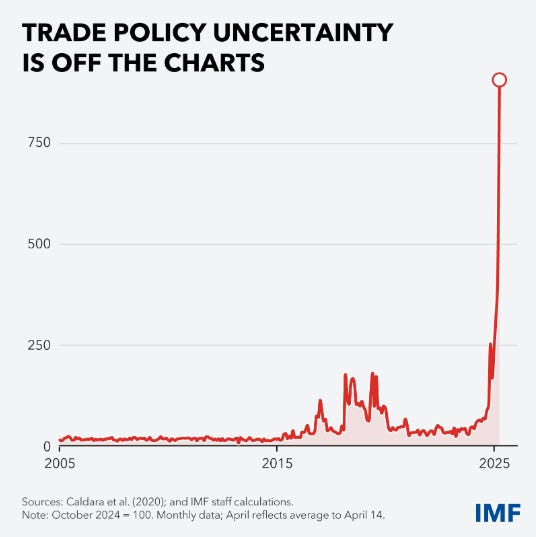

Do we really know anything? Everyone has flagged this chart from Georgieva’s speech last Thursday showing just how much policy uncertainty has increased. I feel like all the estimates in the report deserve a disclaimer that it’s quite likely that they are likely to be further off from accurate than usual given the high levels of uncertainty.