Food Prices - May 2020

While global food prices are declining, Latin America and the Caribbean face an increase in food insecurity

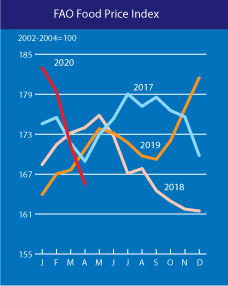

The FAO Food Price Index fell for the third consecutive month in April. This index is a variable that I monitor regularly because there is a statistical correlation between higher food prices and protests.

However, like so much else in 2020, the implications of this drop are complicated by coronavirus.

The Food Price Index is global and may not capture localized rises in food prices. In particular, food prices in Brazil and Mexico have increased in the past month.

Separate from the official statistics, the perception across much of the region is that food prices have increased. For example, a survey by the WFP shows 59% of respondents in the Caribbean believe food prices have increased.

Coronavirus has disrupted supply chains, meaning local disruptions that deviate from the global trend are more likely. With borders closed, flights cancelled and global shipping down, countries facing lower supplies and higher prices can’t import more food from countries where food prices have fallen.

The devaluation of emerging market currencies means some prices have increased in local currency, even as they have decreased in dollars. This is particularly true in Mexico, where the peso has dropped over 20% this year and which imports a significant amount of food from the US in dollars.

The economies of food exporters, particularly Brazil and Argentina, are going take a hit from lower commodity prices in the coming months.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, most economies in Latin America have a large informal sector that has lost a significant portion of its income. So even where food prices are falling, food has still become unaffordable for the poorest. A recent WFP report highlights the facts that rising food insecurity was already a serious issue in Central America even before the most recent health crisis. Coronavirus related economic damage will particularly impact Venezuelan migrants throughout South America.

That last point has meant rising food insecurity across the region in both rural and urban areas. To the extent that we can explain the correlation between high food prices and protests, it generally relates to whether or not large portions of the population can put food on their tables. The price-protest correlation has never been a perfectly predictive measurement, but is even less likely to hold up in this year’s health emergency and economic decline.

All of this is to say that even if food prices are falling globally, that trend isn’t holding true Latin America’s biggest economies and the region’s political stability is unlikely to benefit from the price drop.

Food insecurity is increasing in the context of economic recession

For context, the region is likely to face its largest economic decline in decades. The chart below from ECLAC comes from a late April presentation. It’s possible that growth figures may still be revised downward.

According to the IDB, that economic decline will hit the poorest households the hardest and those working in the informal economy will be less likely to receive government assistance.

Thanks for subscribing and reading

Please feel free to email me with questions or comments.