Colombia Security Notes - September 2024

The ELN and Gaitanistas control territory, tax local businesses, campaign for local support, and generally harm Colombia's economy.

Two articles published this week about Colombia provide critical context to the investment and security environment there. Matthew Bristow at Bloomberg reports on the ELN attacks on oil infrastructure near the Venezuelan border. Elizabeth Dickinson from the International Crisis Group writes an op-ed in the New York Times about the Gaitanistas or Gulf Clan near the border with Panama. Go read both articles. Here are seven takeaways:

Criminal groups "taxing" local businesses drives the profits, the crime, and the strategic challenge.

Beyond the key point of the Bloomberg article highlighting ELN attacks against oil infrastructure, the criminal groups increase the cost of doing any sort of business in Colombia.

Bloomberg:

Shakedowns from the ELN have made Arauca among the most expensive places in Colombia to do business, according to Juan Ricardo Ortega, the company’s chief executive officer.... The ELN sets fire to trucks and buses operating in its territory without its permission. Even if big companies don’t make payments to the group, their subcontractors have little choice, pushing up the price of everything from transport to security services, Ortega said.

NYT:

The Gaitanistas’ reach for territorial domination is financially motivated. After taking over an area, the group monetizes every aspect of life. Businesses located on Gaitanista-controlled land must pay a tax or face violent consequences. Farmers told us they were obligated to pay for every cow they owned or sack of potatoes they produced. Even development projects are extorted, with the Gaitanistas charging a percentage on government infrastructure contracts. The group also charges a tax before migrants cross the Darién Gap, which more than half a million people traversed last year.

This is a security challenge that goes beyond the drug war.

Note the lack of cocaine in both articles. Drug production and trafficking are not a driving factor in the violence nor a key portion of the financial revenue mentioned for either group. Yes, both have some involvement in cocaine trafficking, but it is a very limited part of their operations and mostly a business of opportunity. If cocaine disappeared tomorrow, neither would be significantly impacted. These aren't drug cartels pretending to be rebels the way the FARC were and are today (the various FARC offshoots still fighting are heavily involved in cocaine manufacturing and trafficking). The ELN and Gaitanistas organizations are operating in a post-drug war environment and they are thriving. Ending the "drug war" doesn't magically bring security.

Borders matter.

Even if drug profits aren’t the key source of revenue, many of the extortion schemes and other illicit trafficking activities exist because these groups operate so close to borders, ports, and infrastructure that is critical for supply chain logistics. It’s an obvious point made many times before, but one worth repeating.

Criminal groups engage in social investment to gain local support and launder extortion money.

Both groups invest in local infrastructure and services as a way of obtaining support from the local populations.

NYT:

One favored method is for social organizations that are sympathetic to some of the ELN’s objectives to organize strikes to pressure a company into paying for projects such as paving a road or building a health clinic. The guerrillas then get the credit for bringing investment to areas abandoned by the government, while also taking a cut for themselves.

Bloomberg:

Alarmingly, many large businesses and landowners have come to prefer having the Gaitanistas around because they offer protection from other armed groups who may kidnap, steal or extort with less discipline. This symbiosis gives the Gaitanistas deep and permanent roots in the society.

Colombia’s security challenge is about real territorial control

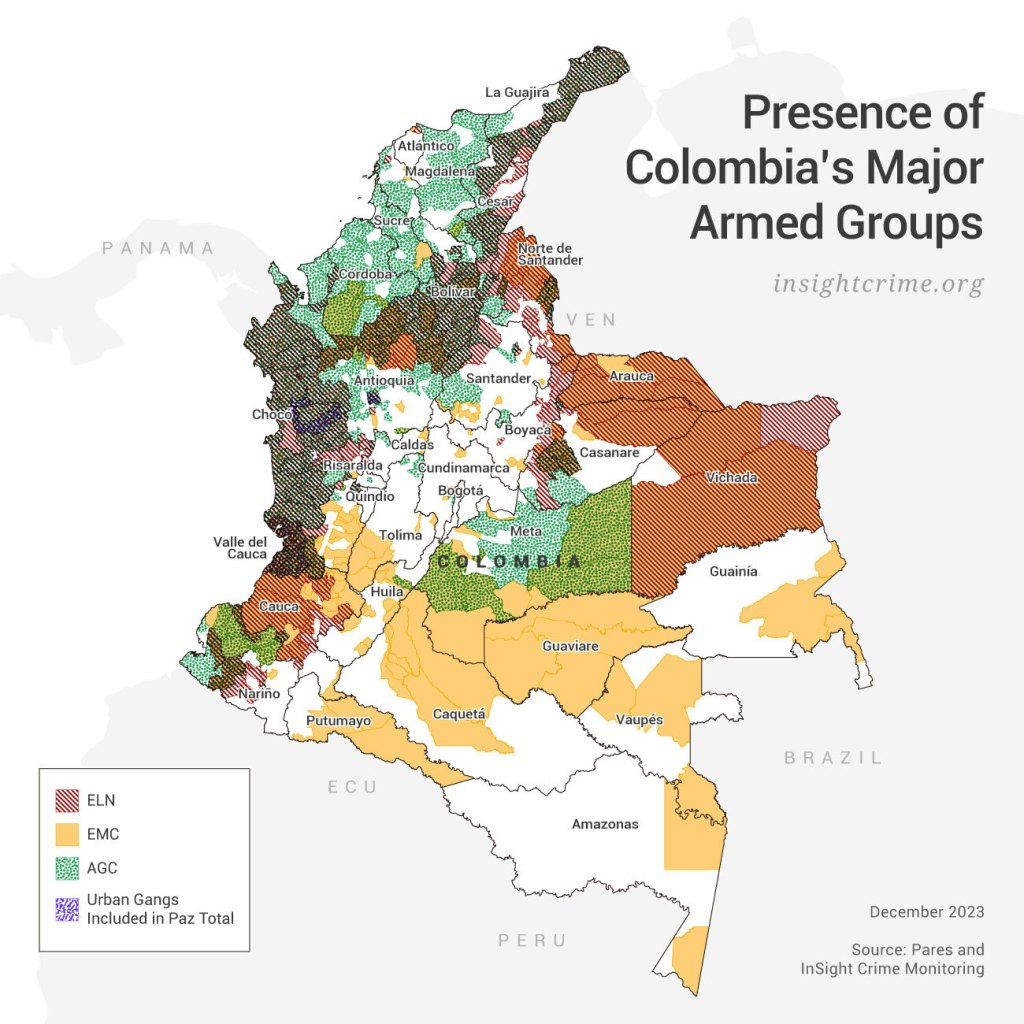

This map from InSight Crime shows the territorial control of Colombia's various criminal groups. It's important to differentiate that territorial control here means something different than it does when you see similar maps of Mexico. In Mexico, there are violent cartel organizations that control drug trafficking routes and extortion networks in plenty of places, but the government has parallel control of most of the major municipalities, etc. In some cases in Colombia, this is actual territorial control. The ELN and Gaitanistas control ground where the government has minimal presence and these groups are the "monopoly on violence" in the region.

Understanding that difference in how criminal groups manage territory is important for why the security context is so different and why companies may be more willing to invest in Mexico, where violence is in many cases worse, than they are in Colombia.

Petro's security policies aren't working, but we may not know why.

A recent report from Colombia Risk Analysis highlighted an Invamer poll showing 85% of Colombians believe the security situation is worsening and 66% believe Total Peace is on the wrong track. The security failures are a drag on his government's popularity (see my column last week about the first two years of Petro’s term) and prevent him from accomplishing other goals.

The big question worth asking: Is this a strategic failure or an implementation failure? Or is it both or is it neither? It could honestly be any of those four options. Perhaps total peace is a strategy that cannot work in any format. Perhaps Petro's lack of focus combined with a poor mix of sticks and carrots in negotiations is to blame. And it could be that total peace is a strategic failure and Petro is just bad at governing, but putting that aside, these groups would be gaining under nearly any other strategy or leader because security is hard and these groups have the financial means to keep fighting.

The lack of security holds back Colombia's economy.

The government should work harder to understand why its security policies are failing because the "tax" on businesses operating in criminally controlled areas holds back foreign and domestic investment. It's a negative spiral. Companies are hesitant to invest because of the security situation; the security situation won't improve without greater investment that meets the needs of the people and allows the government to be present. Breaking that security/investment paradox should be near the top of the government's agenda if it wants to succeed in the coming two years.